Read our market review and find out all about our theme of the week in MyStratWeekly and its podcast with our experts Axel Botte, Aline Goupil-Raguénès and Zouhoure Bousbih.

Summary

Listen to podcast (in French only)

(Listen to) Axel Botte’s podcast:

- Review of the week – Financial markets, Trump Makes Waves at Davos, Beware of JGBs;

- Theme – House of (Credit) Cards.

Podcast slides (in French only)

Download the Podcast slides (in French only)Topic of the week: House of (Credit) Cards

- In the United States, the use of credit cards has become an essential means of financing household consumption. Households have the option to pay off their balances at the end of each month or carry them over, facing interest rates exceeding 20%. Approximately 60% of households revolve their debt for over a year;

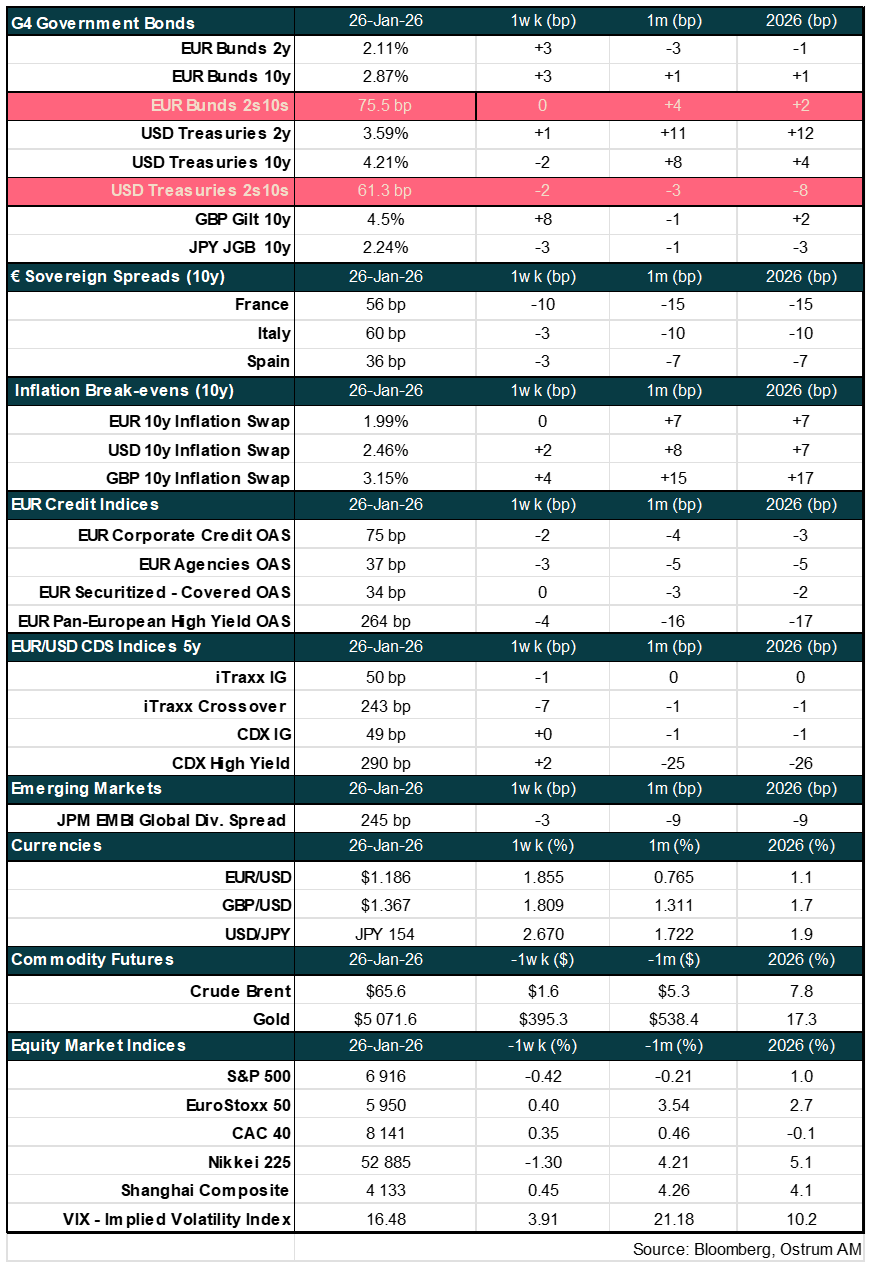

- According to a survey by the New York Fed, payment delinquencies exceeding 90 days have now reached levels comparable to those seen during the global financial crisis. The rise in payment delays continues alongside an increase in borrowed amounts, which now exceed $1.3 trillion;

- Donald Trump has proposed capping interest rates at 10% for a duration of one year. However, the real question is why households remain so insensitive to interest rates despite the existence of cheaper financing alternatives. The effective marketing strategies employed by banks appear to be a contributing factor;

- Furthermore, banks are reporting very low default rates compared to the household survey conducted by the Fed/Equifax. This substantial discrepancy may obscure an underrepresentation of the risks borne by the banks.

Beware of credit card balances rising with delinquencies

Credit card balances top $1.3 trillion.

In the 3rd quarter of 2025, household debt balances increased by $197 billion in the September quarter, a 1% rise from the second quarter of 2025 (according to the NY Fed’s quarterly report on household debt and credit). Balances now stand at $18.59 trillion, up by $4.44 trillion since before the pandemic. Whilst the bulk of household debt is mortgages ($13.07 trillion), we take a look at other consumer loans. In total, non-housing balances increased by $49 billion, a 1.0% increase from July to September.

Credit card balances rose by $24 billion in the 3rd quarter and now total $1.233 trillion outstanding (+5.75% year-on-year). Other consumer loan balances, including retail cards and consumer finance loans, rose by $10 billion to $550 billion.

In a troubling trend, American households keep accumulating credit card debt in the context of rising delinquencies. As can be seen in the chart above, in the 2009-2010 financial and economic crisis, aggregate credit card balances declined (by $190 billion) as households struggled to manage their bills, and late payments increased (10 to 14% of balances). The current increases of both balances and delinqencies highlight a transition from credit card use as a convenience to an essential financial lifeline amid rising prices and lackluster labor market prospects. It is estimated that a significant portion of this debt—73%—is tied to everyday essentials.

Two kinds of credit card users

Cardholders face high interest charges if they choose not to pay their credit card balance at the end of the month.

Credit cardholders have the option to pay off their balance at the end of the months. There are thus two kinds of clients for credit card issuers. Some people (‘the transactors’) pay off their credit cards at the end of each month. They use the cards as a payment method and collect points and rewards and never have to pay any interest. For other users (‘the debtors’), who revolve their debt and don’t pay off their monthly balances, interest charges can be very high and indeed much higher than what would be expected based on a user’s credit risk. Furthermore, long-term credit card debt is becoming more common, with 61% of cardholders in debt for over a year. The median interest rate on credit card is indeed 25.3% at present. The growth in credit card debt is not limited to low-income individuals. Higher earners are also carrying substantial balances and are often reluctant to seek help due to stigma. Increasing cost of living and the end of the memorandum on student loan payments in 2025 have pushed more families to rely on credit cards, raising the risk of defaults.

With U.S. mid-term elections looming in November, the political discourse surrounding high credit card interest rates has intensified, with Donald Trump calling for a 10% interest cap on new ‘Trump cards’ as a potential relief for borrowers. It is a fair question to ask why card issuers can get away with charging usury-level interest rates. What are borrowers really paying for?

Interchange or swipe fees are close to 2% of transaction value.

First and foremost, credit cards are a very profitable business. The return on assets for credit card businesses hovers about 3.5-4% compared with 1.2% for U.S. banks in general. The primary reason for high profitability is high interest rates. But there are other sources of revenue. Credit card swipe fees are fees charged to merchants each time a customer makes a purchase using a credit card. These fees are typically expressed as a percentage of the transaction amount plus a flat fee per transaction. Interchange (or ‘swipe’) fees can make up to 2% of transaction value. Of that, 15-20 bps go to the payment companies (Visa, Mastercard) and card issuers collect a fee from the retailer based on the transaction value. Aggregate transaction value is in the vicinity of $10 trillion. There are many fintech companies doing Buy Now Pay Later and other forms of payments that attempt to grab market share in the card payment business (Visa has 70% market share, Mastercard is big too).

Why do banks get away with 20% interest rates on credit cards ?

Cardholders are less sensitive to rates than marketing, rewards.

Hence interest rates (23% on average) are the main source of revenue for credit card issuers. Interest income is much higher that banks pay on all sorts of liabilities including deposits, short-term money and bonds. In turn, average charge-off rates on revolvers (the ‘debtors’) are about 5-6%. There is thus an 18% average excess spread or risk premium, quite a deal for banks. Default rates may spike occasionally, but not for long. People don’t default that much, so to speak. With credit card delinquencies within 6%, average risk premiums on 800 FICO credit scores must hover about 500 bps, and around 900 bps on 600 FICO. Credit card lending is nevertheless unsecured. Hence, households facing financial difficulties may prioritize mortgage or car loan payments over credit cards. One must live somewhere and drive to work. In times of crisis, one should expect a larger share of bank losses to come from credit card lending rather than secured lending (most of bank balance sheet is low-risk and boring albeit leveraged).

The credit card business is remarkably sticky. Consumer loyalty plays a big role. Cardholders like to collect airline miles and other rewards, which they (mainly the ‘revolvers’) pay for dearly. There is thus effective discrimination among cardholders based on their credit card usage. About 75% of $150 billion annual interchange fees fund reward programs, with banks pocketing the rest. There are strong network effects which force retailers to ‘eat’ the fees.

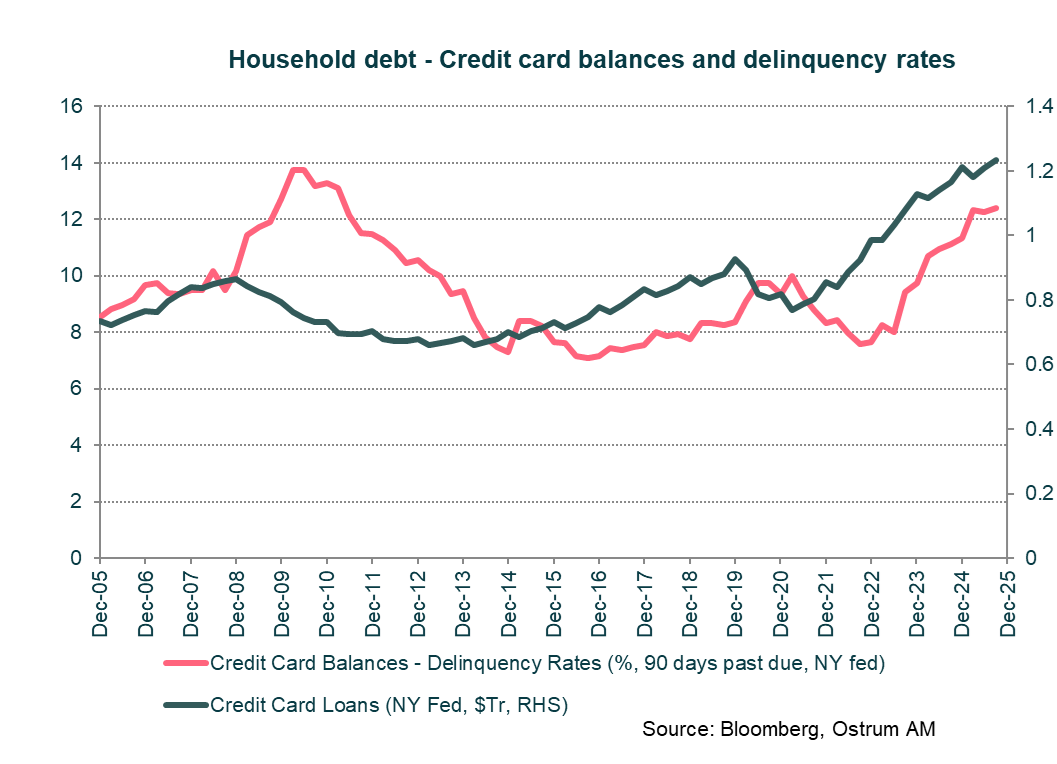

There are currently close to 650 million credit card accounts used by 132 million U.S. households. But, consumer loyalty requires a lot of advertising from credit card companies. American Express spends about $6 billion on advertising each year, Capital One about $4 billion. That’s more than big spenders including Nike or Coca-Cola invest annually. Advertising and mailing cards directly to households is very effective indeed to push cards to debt junkies. They do that because it works. And it works because U.S. households are not sensitive to interest rates charged on credit cards. Households may pay a great deal of attention to the interest rate on their mortgage or car loan but not on credit cards. For instance, credit unions offer much cheaper credit cards but have a hard time gaining market share as households don’t hear of them. Buy Now Pay Later fintech companies also struggle with high customer acquisition costs despite being online and visible to customers. They have not disrupted the business for now. When marketing works, grabbing market shares is difficult. This also explains why Fed policy rates cannot reach every corner of the U.S. economy: it is quite clear that +/- 50 bps on policy rates won’t move the needle in the cards business.

As more households fall behind on credit card payments, there should be an incentive for them to find cheaper sources of unsecured financing. Personal lines of credit are cheaper than credit cards and the money received upfront can be used to clear existing credit card balances. Prior to the 2008 housing collapse, HELOC (Home Equity Lines Of Credit) had been used extensively (to the tune of $713 billion outstanding in the 2nd quarter of 2007) to fund consumer spending and/or pay off debt. With very elevated housing prices currently, homeowners may use equity in their home as collateral. HELOC debt outstanding reached $422 billion in the September 2025 quarter, up $100 billion from 3 years ago.

Would a cap on interest rates work?

Capping rates may or may not work

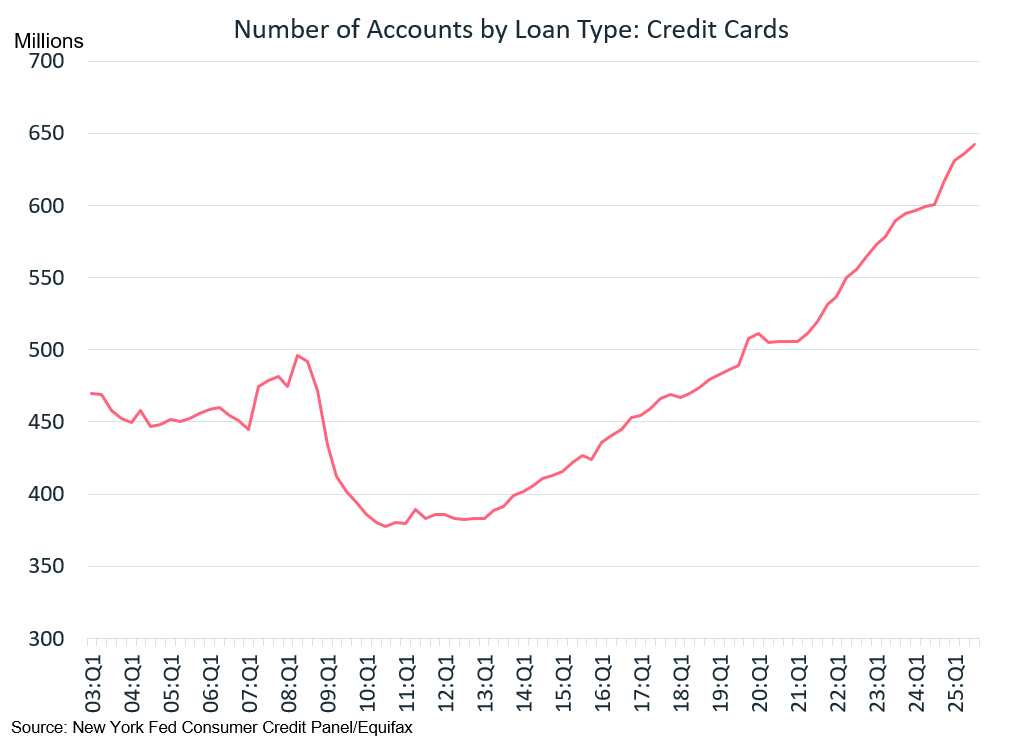

Donald Trump is calling for a cap at 10% on interest rates charged by credit card issuers for one year. The move is politically motivated months ahead of the mid-term elections but it is a legitimate question to ask whether a cap would provide relief to consumers. Stocks of credit card businesses faced steep declines following Donald Trump’s comments on a potential interest rate cap for one year on January 9th and the reduction in swipe fees on January 12th.

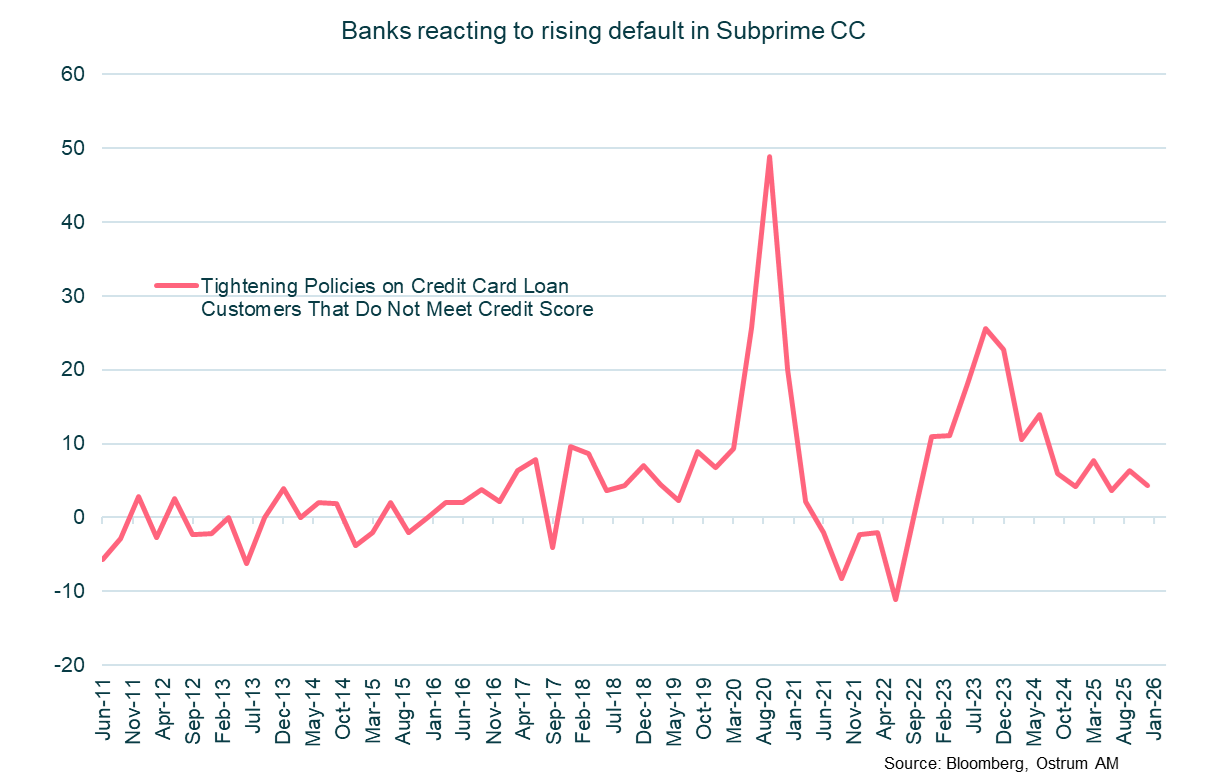

However, financial institutions have warned that such a cap could lead to increased fees and tighter credit standards. The Fed’s Senior Loan Officer Survey points to moderately tighter credit standards on credit cards over the past few quarters. For borrowers below the required credit score (i.e. the less creditworthy households), tighter conditions have applied and anectodal evidence point to penalty rates being enforced more quickly. Forcing rates lower could hence provide relief for some wealthy households with large outstanding credit card balances but engineer a credit crunch for lower-income households.

The devil is in the detail

Banks report minimal delinquencies, whilst NY Fed data are through the roof.

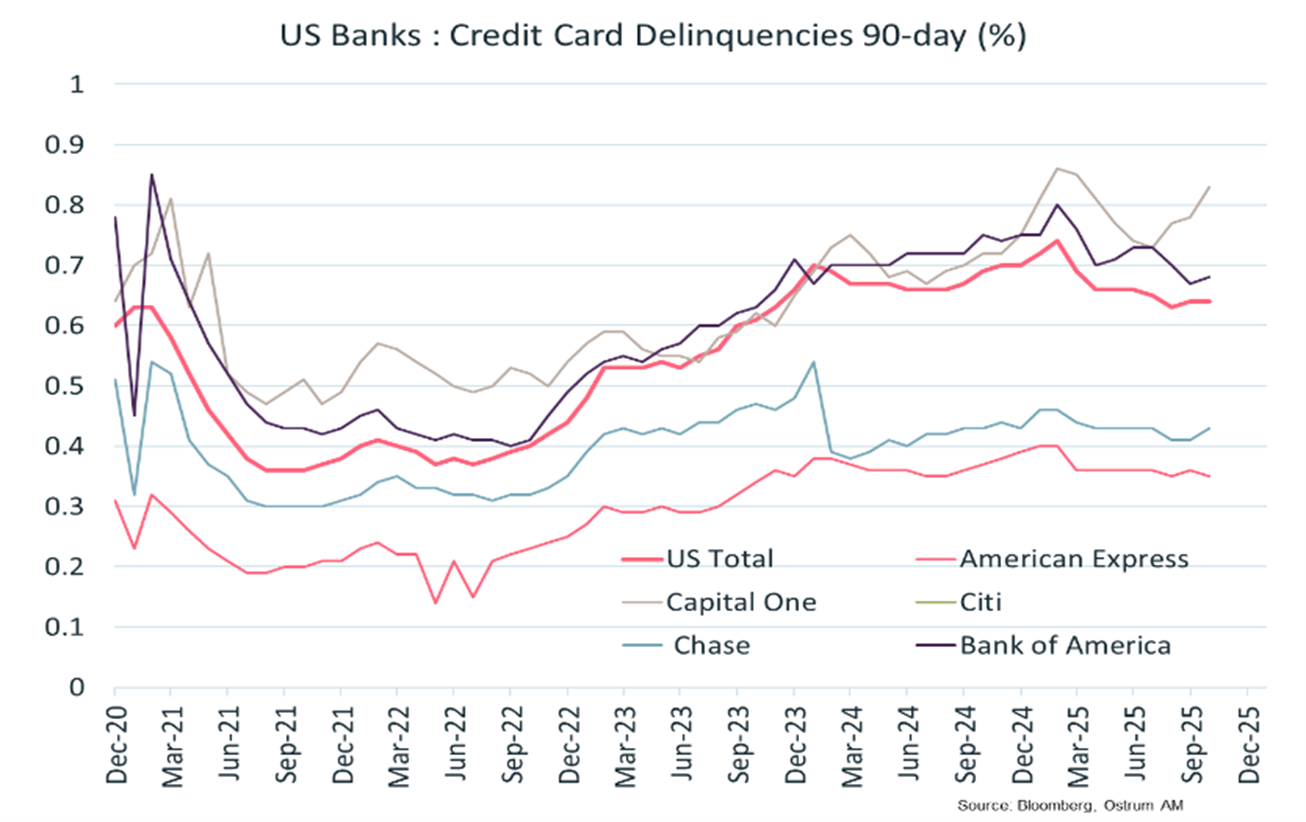

It is worth noting that credit card companies report much lower delinquency rates than anonymized individual data from the New York Fed/Equifax quarterly survey. The larger U.S. lenders may screen out bad credits better than the competition or have a higher-income customer base (think of the likes of American Express) than the smaller competition. But, there is a striking difference between the double-digit delinquency rates shown in the New York Fed report and the sub-1% 90-day delinquency rates reported by the main U.S. financial institutions (see chart below). Credit card issuer trust data report similar benign defaults.

It could be the case that individuals are falling behind on payments, but banks still consider these borrowers current and creditworthy. Households may have multiple credit cards and failing to pay off a balance by “accident” may happen… but only up to a point. Let’s keep an eye on these developments as finance History is indeed filled with misrepresentation of risk by lenders. For the time being, spreads on AAA-rated credit card asset-backed securities are trading at multiple-year lows, much like other securitizations and risky debt including high yields.

Conclusion

The U.S. credit card lending is a very profitable business. Insane interest rates above 20% are clearly much higher than would be justified by underlying default risk. U.S. households however appear insensitive to elevated interest rates, even as 60% of users revolve their balances at penalty rates each month. The marketing of credit cards is very effective and contributes to the worrisome buildup of debt balances even as delinquencies rise. Bank reports paint a rosier picture of delinquencies. More work may be needed to understand this discrepancy in risk reports

Axel Botte

Chart of the week

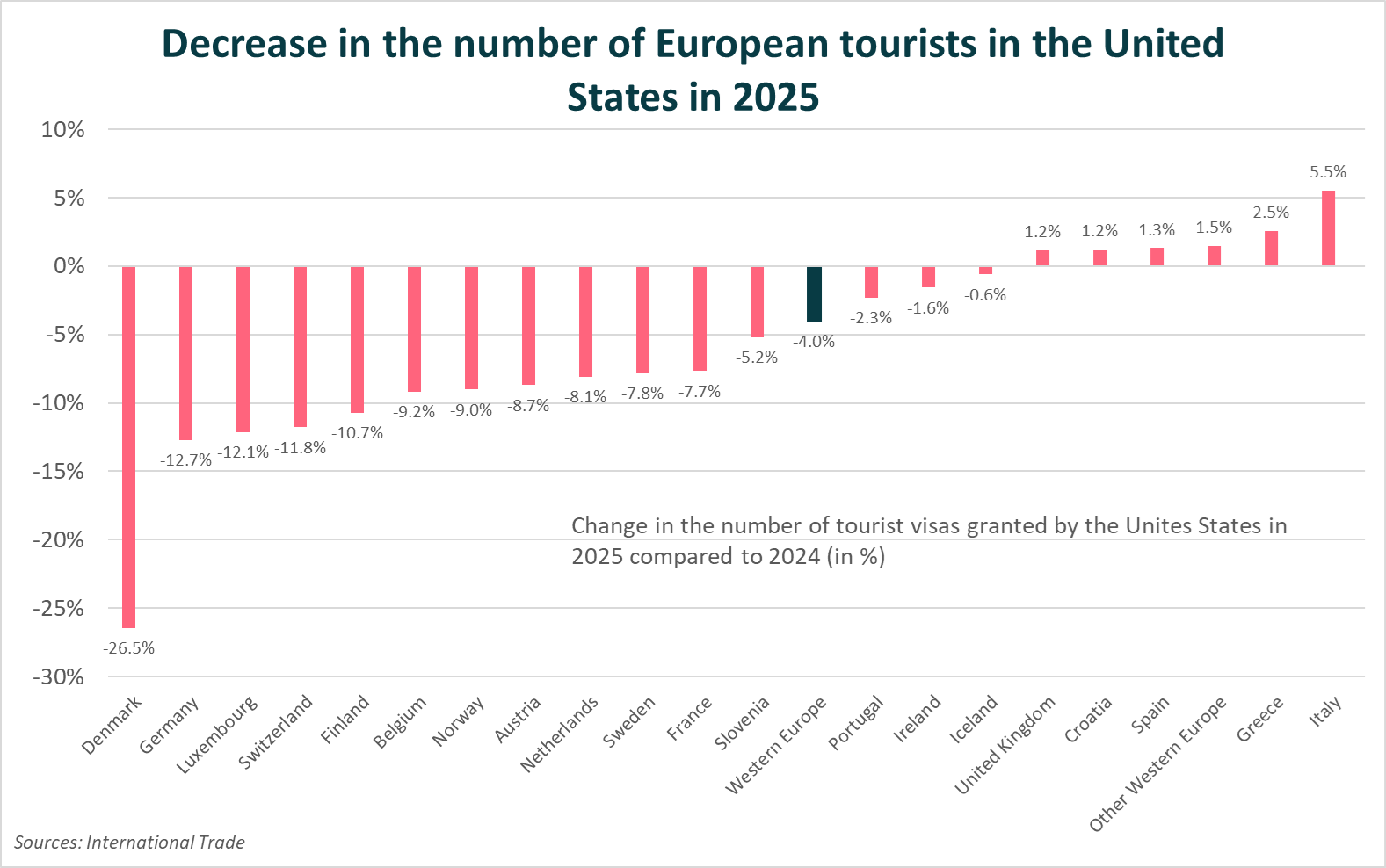

The tourism sector in the United States is experiencing a significant decline in the number of foreign visitors in 2025. The total number of European tourists is down by 4%, with a double-digit decrease in German tourists. The number of Danish tourists has plunged by 26%. However, there is an increase of approximately 1% to 5% in tourists from Spain and Italy.

Despite a stronger euro (averaging $1.08 in 2024 and rising to $1.13 in 2025), it appears that the current administration’s foreign policy is clearly a barrier to tourism in the United States. Nevertheless, the leisure sector continues to hire, even amid a sluggish labor market.

Figure of the week

18.4

18.4 % is the French household savings rate according to a Banque de France estimate.

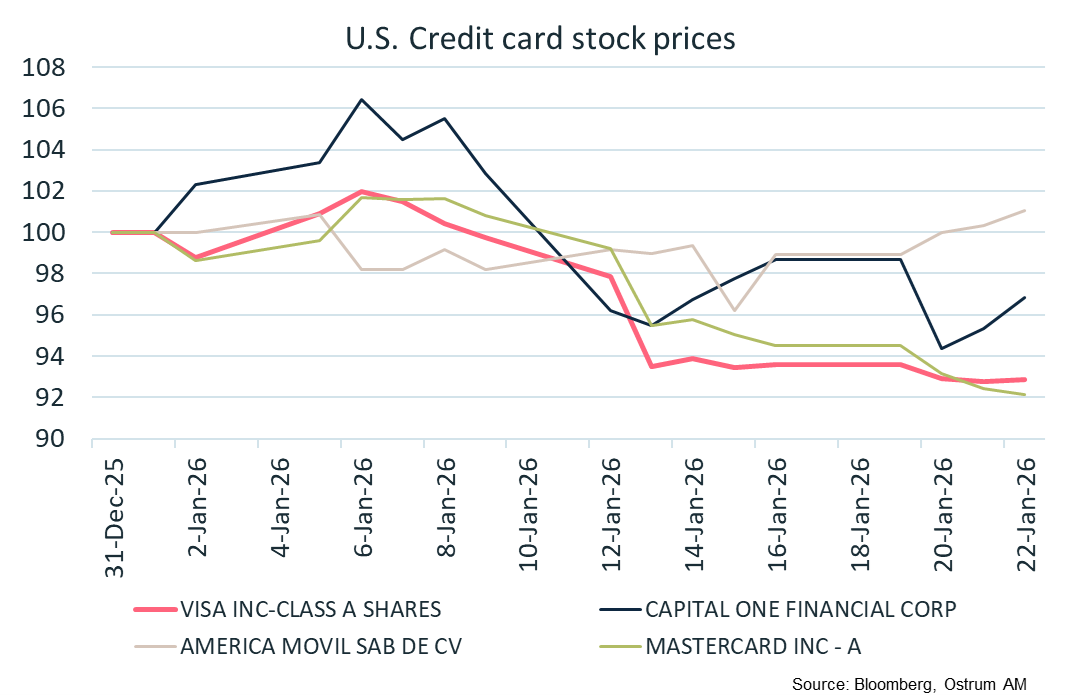

Market review:

- United States: Tariff threats and the Greenland invasion dissipate;

- Markets: The 'Sell America' theme reemerges;

- Equities: Transient volatility, yet the gains from the early weeks have been erased;

- Fixed Income: The implications of the Japanese bond market crash warrant close monitoring.

Noise and Signal

Asset management often hinges on the ability to differentiate between daily noise and the signals that dictate financial trends. In this context, the volatility induced by Trump’s rhetoric has given way to a rebound in equities and renewed pressure on long-term interest rates and gold.

Donald Trump's address at Davos, which primarily targeted Europe, captured market attention. Yet, a degree of de-escalation ensued, as the U.S. President appeared to rule out military intervention in Greenland and ultimately retracted the tariff threat against eight European countries. The notion of TACO—Trump Always Chickens Out—surfaced once again, coinciding with a resurgence of pressure on U.S. long-term interest rates. Conversely, the ambitious fiscal plans of Sanae Takaichi, which propose a stimulus equivalent to 3% of GDP, present a tangible signal: rising Japanese yields could disrupt global investment flows. Indeed, international tensions frequently rekindle a domestic bias in asset allocation.

From an economic perspective, U.S. growth in 2025 has surpassed expectations. The GDP growth for the third quarter stands at 4.4% at annualized rate, bolstered by robust consumer spending and a notable reduction in the trade deficit, driven by an unexpected surge in service exports, among other factors. However, the decline in consumer spending observed at the end of the third quarter has moderated as of November. Household income is slowing down amid a deteriorating labor market, and inflation remains elevated at 2.8%, according to the PCE deflator, significantly above the Fed's target. Politically, the budget bill passed by the House of Representatives could help avert another shutdown at the end of the month but the tragedy in Minneapolis over the weekend may put DHS/ICE financing at risk. In Europe, surveys indicate a cyclical improvement, particularly within the manufacturing sector, with the composite PMI for January holding steady at 51.5.

In financial markets, the announcement of tariffs (which sparked a 2% drop), followed by its withdrawal, dictated the movements of stock indices. Bank of America, however, has noted outflows from U.S. equity funds, a reflection of the 'Sell America' sentiment witnessed last April. Long-term rates briefly rose to 4.30% before retreating to 4.23% by week's end. The prospect of massive U.S. Treasury bond sales by European institutions appears incongruous, considering that these are predominantly mutual fund holdings rather than reserve accounts or sovereign wealth assets. Conversely, the turmoil in Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs), with 30-year yields peaking at 3.88% during the week, is likely to trigger significant capital movements at some point. Japan's second-largest bank, Sumitomo, has indicated a preference for Japanese debt over foreign bonds. In the Eurozone, the Bund is flirting with the 2.90% threshold, with tension on rates tightening spreads on both sovereign debt and credit. Despite active trading in the primary market, there seems to be no impact on spreads; the OAT trades at 65 basis points over Bunds following the activation of Article 49.3 to pass the French budget. Swap spreads remain stable. High-quality credit remains well-positioned with spreads over swaps narrowed to 63 basis points, and covered bonds auction under 22 basis points against swaps.

Axel Botte

Main market indicators